2016 is a flat circle

"Everything we've ever done or will do, we're gonna do over and over and over again." Yupppppp ...

Of course this was going to happen. Sooner or later, the people who have spent the last year and a half telling us that Robert Mueller's pointless special counsel investigation of non-existent — excuse me, no doubt just hitherto unveiled — collusion between Donald Trump's campaign and a mysterious amorphous entity known as "Russia" was nothing but a political hit job were going to decide that they, too, would like to have a go at investigating something for a year or two.

If the new special counsel investigation of the FBI's decision in 2016 to end the investigation of Hillary Clinton's use of a private email server — another investigation of an investigation of something that happened years ago — proposed by House Republicans on Tuesday began tomorrow, how long would it last? A year and a half? Two? I think the answer is obviously "long enough to be relevant in 2020." And why not? The 2016 election is never going to end.

Let's be honest. No Republican actually ever cared about Clinton's supposed violations or near-violations of bureaucratic norms governing the use of communications technology. These are things that nobody except a handful of law-enforcement officials and people in our intelligences services know anything about, much less understand and make the subject of impassioned debates. The point was that it made Clinton look bad. If the same concerns had been raised about a former Republican secretary of state they would have been dismissed as empty proceduralist noise-making, which, indeed, is exactly how they were treated by Democrats, including Sen. Bernie Sanders, who is nobody's idea of a team player.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Which, in turn, is why Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C.) and other members of the House Freedom Caucus, a body well known for its almost romantic attachment to ill-defined bureaucratic norms, care enough to insist upon an investigation of the FBI's decision not to prosecute her over these hiccups years later. Partisans on one side or the other will solemnly insist that this is either a pressing matter requiring the full cooperation of the relevant federal agencies and all involved actors — and worthy of whatever demands it makes upon the public — or a waste of time and money. Journalists too will take their cues accordingly and either genuflect before the altar of procedure or work themselves into a fury about the vile cynicism of the GOP.

The fact that politicians feel compelled to play these games is one thing. Why can't the rest of us be grown-ups about it? Everyone knows that the FBI, like every other organization in the world, is made up of individuals who have political views. Did you know that there are federal bureaucrats who would prefer to have a center-right Democrat in the White House rather than the former star of The Apprentice and that if it is within their power they might be expected to take or fail to take certain actions that could bring about this desired outcome? Imagine how much more pleasant the world would be if we all calmly accepted this reality the way we do a thousand other things we find unpleasant or inconvenient.

The bad-faith obsession with the conduct of the FBI here is similar to the conversation we often have in this country about so-called “gerrymandering,” which is polite liberal code for winning at politics. Both sides want to have maps of districts drawn in a manner favorable to their candidates. It's not a victory for the powers of light against the force of darkness when they get changed one way or the other any more than it is a blow for justice when a political appointee is caught out for lying about an insignificant meeting or when some FBI agents decide not to make investigating the woman they want to see in the White House their top priority.

If this all sounds repulsively cynical, my answer is that it is meant to sound that way. The political process is not a middle-school civics class; it is about winners and losers playing a game whose rules are known to everyone involved. Pretending that the code according to which it is played is a much loftier thing than it really is or that the stakes are the same thing as the common good is not inherently objectionable. But it should be pointed out that it is a form of participating in the game rather than a way of observing it.

Phony outrage, concern-trolling, tone-policing, and selective obsession with procedural norms are what define American politics. The 2016 election is not going to end until this changes. I'm not holding my breath.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

Italian senate passes law allowing anti-abortion activists into clinics

Italian senate passes law allowing anti-abortion activists into clinicsUnder The Radar Giorgia Meloni scores a political 'victory' but will it make much difference in practice?

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

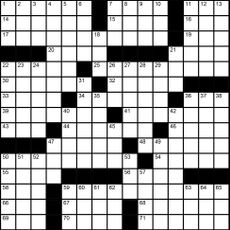

Magazine interactive crossword - May 3, 2024

Magazine interactive crossword - May 3, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - May 3, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Magazine solutions - May 3, 2024

Magazine solutions - May 3, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - May 3, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published