The Lorena Bobbitt case was a blueprint for how men would dismiss #MeToo

From gaslighting to crude jokes

"For this show, we're not dismissing Christine Ford as a liar," Fox News host Tucker Carlson began one evening last September. "It doesn't seem like she is. It seems like she sincerely believes everything she is saying. But that does not mean she is right."

Having just finished watching Lorena, Amazon's new four-hour docuseries on Lorena Bobbitt, I revisited Carlson's dismissal of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh's rape accuser and found it particularly chilling. In the 25 years since Bobbitt allegedly endured brutal violence at the hands of her husband, John Wayne Bobbitt, before famously committing "the one act every man fears most," one would have hoped that we'd be better at examining such incidents from the woman's perspective. Instead, Lorena sheds light on how the Bobbitt case proved to be a blueprint for the next two decades of male backlash against women accusers.

Lorena Bobbitt (who now uses her maiden name, Gallo) and John Wayne Bobbitt became worldwide tabloid sensations when Lorena cut off Bobbitt's penis with a knife after he allegedly raped her in 1993. Bobbitt's organ was recovered by police and surgically reattached; Gallo herself was found not guilty of wounding Bobbitt due to an "irresistible impulse" plea. In her trial, which is documented extensively in Lorena, out Friday, Gallo described being physically beaten by her husband as well as repeatedly raped over the course of their marriage — allegations that the documentary takes care to back up, although Bobbitt maintains his innocence to this day.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In 1993, much like now, many men had little empathy for the female accuser. In the Bobbitt case, part of that lack of understanding was due to the unique nature of Gallo's act: As Lorena illustrates, there was a fanaticism around the nature of the body part that was removed. "She took away the thing that means the most to a man," Bobbitt's brother, Todd Biro, declared on one talk show. A contemporaneous interviewee told The New York Times that Gallo "ought to be executed" for what she did to Bobbitt.

While Gallo's act was indeed shocking, such preposterous statements only serve to show that when it comes to women's allegations of rape and abuse, much less her acting out in self-protection, there is a fixation on what the woman did, rather than on what the man might have also done. And while the recent #MeToo movement contains no drama quite like Gallo's violent and impulsive defense, two decades have done very little to repair this war of perspectives.

Even as Bobbitt's supporters painted Gallo as crazy and vengeful, women felt differently: "We're thinking, God, what did he do to make her do something like that?" one of the nurses who attended to Bobbitt's wound said. Women who had been similarly abused or raped saw Gallo as a hero, with Gallo recalling overhearing one say "someone did what I always wanted to do." Yet the former president of the National Organization for Women, Kim Gandy, explained that on the whole "the public was so entranced by" Gallo's act that they couldn't see "what might have driven a victim to do what she did." Gandy added that the domestic abuse story behind the incident was largely ignored by the media because it was male editors who were shaping the coverage.

In fact, many men following the Bobbitt case had the opposite response of women, putting themselves in Bobbitt's shoes. "You know, oh man, I started thinking about my wife," the crime scene technician told Lorena's filmmakers. Bobbitt became a celebrity especially among men after his recovery, appearing on Howard Stern and other talk shows, signing autographs, and eventually making a minor career for himself as a porn star. As one dismayed op-ed read: "He beats his wife and is a celebrity. God help us all." It's a nauseatingly familiar sentiment for many who have watched #MeToo unfold these past couple years.

The excuses made by Bobbitt's allies are still being made today. One common joke, for example, is that a victim isn't attractive enough to rape. "I don't even buy this whole thing that he was raping her and stuff," Howard Stern said on a show on which Bobbitt was a guest. "She's not that great looking. She's got a lot of pimples, your ex-wife." Such a refrain would return in 2016 when then-candidate Donald Trump brushed off accusations of sexual assault, implying his accusers were too unattractive.

Gaslighting is also used to diminish allegations. "When Mr. Bobbitt did what she perceived as a rape, that was a challenge to her sense of control," Dr. Evan Nelson, the Virginia state forensic psychologist, argued at Gallo's trial, raising the question of whether it had been rape at all. His words feel eerily like Carlson's claim that Ford couldn't be relied on to know if she was assaulted by Kavanaugh or not. Likewise, statements of I don't remember that happening or I don't remember it happening like that from men, often framed in the form of an apology after an allegation, echo the unspoken threat that it is the woman who somehow got it all mixed up.

Then there is the general lack of equal perspective paid to both parties. "I feel so badly for [Kavanaugh] that he's going through this," Trump said last year; of course, no similar concern was paid to Ford for going through the same public scrutiny and painful excavation of memories. The disinterest in Gallo's side of the story was also widespread in 1993. "The pain was going through my mind, for Christ's sakes, for this poor guy," one interviewee told a news crew. The former executive director of the National Center for Men went as far as to tell the Times, "This is the result of feminists teaching women that men are natural oppressors." It is not such a giant leap from there to calling accusations a "witch hunt."

The lapse in male understanding could simplistically be explained away; as Gallo herself pleaded to lawyers at her trial, "He was hurting me. I couldn't stand it. I can't describe it. Maybe you don't understand, because you're a man." But the intervening decades of excuses for men by other men are indicative of a lack of understanding beyond just physiological empathy. With history repeating itself in #MeToo, all these years after the Bobbitt case, it is horribly clear we still have a long, long way yet to go.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

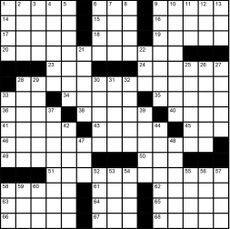

Magazine interactive crossword - April 26, 2024

Magazine interactive crossword - April 26, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - April 26, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Magazine solutions - April 26, 2024

Magazine solutions - April 26, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - April 26, 2024

By The Week US Published

-

Magazine printables - April 26, 2024

Magazine printables - April 26, 2024Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - April 26, 2024

By The Week US Published