Why an erstwhile neoliberal is feeling the Bern

Bernie Sanders lit the fire of a grassroots movement in 2016. If he did it once, he could do it again.

I almost can't believe it's come to this. I spent most of the 1990s as a neoliberal, the first few years of the 2000s as a conservative, and then every year since 2004 as a Democratic-leaning centrist once again. My political instincts run toward moderation. I'm reflexively hostile to radical politics. Yet here I am, strongly tempted to support lifelong democratic socialist Bernie Sanders for president.

How has it happened? Why am I feeling the Bern?

The answer grows very much out of the peculiarities of the present political moment.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Democrats need to move left in 2020. That much is clear to me. America's two major parties are competing to determine which of them will become the more effective vehicle for the populism surging through the country and the Western democratic world more generally. When President Trump isn't doing the bidding of his party's plutocrats — slashing corporate taxes and gutting government regulations and benefits — he and his advisers talk about turning the GOP into a workers' party. Trump's hostility toward low-skilled immigration, and protectionism on trade (along with his tolerance for and even encouragement of outright racism and xenophobia), are glimpses of what a thoroughly populist Republican Party would look and sound like.

To win decisively against this right-wing version of populism, the Democrats need to offer an alternative — something big and bold that aims to change the priorities of the party and the culture of Washington at a fundamental level. The target must be the market-driven policy outlook that has dominated left-of-center politics since the election of "New Democrat" Bill Clinton in 1992. Ronald Reagan shifted the center several clicks to the right, and both Clinton and Barack Obama found themselves forced to abide by the change. But now rising populist energy and anger are poised to shift the center line back to the left.

At this very early moment, the Democratic field is dominated by candidates tripping over each other trying to prove their progressive bona fides. So, why Bernie? Why not support Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.)? Or Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.)? Or Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.)? If Sanders' candidacy doesn't take off, I'll probably end up cheering on one of them. But there are compelling reasons to start out favoring the independent senator from Vermont.

For one thing, Sanders is the biggest single reason why all those Democrats are positioning themselves so much further left than any national politician has since the 1980s. Sanders came out of nowhere in 2016, giving neoliberal heir apparent Hillary Clinton a run for her money, forcing her to move left to find votes. He lit the fire of a grassroots movement using nothing more as kindling than his passionate denunciation of the injustices and inequities that pervade contemporary American life. If he did it once, he could do it again. Why accept a substitute?

Do I worry about Sanders proposing a wish list of new programs that would require confiscatory tax rates and yet still run the risk of bankrupting the country? Yes, I do. Am I concerned about what might happen if he wins by overpromising and then fails to deliver on the impossibly high hopes of his most devoted acolytes? You bet I am.

But here's the thing: Most of the leading candidates are promising ponies right now. And there's a strong case to be made for doing exactly that at this stage of the game. Just as Republicans make a habit of vowing to fight for drastically lower taxes, an end to the administrative state, the abolition of Cabinet-level departments, and other fairly extreme and unrealistic items straight out of a libertarian fantasy, so Democrats need to make politics a little bit more about goals, aims, aspirations, visions of a future America with very different priorities from the present and recent past. Democrats once oversaw marginal tax rates vastly higher than they are today, and they dared to dream of using that revenue to make the country more just and more equitable. How much is really possible today? We just don't know, and as author Corey Robin has been powerfully arguing, it's incredibly short-sighted to pretend that we do.

Warren has lots of smart ideas along these lines. And unlike much of her competition, she has a long track record of developing and working to implement them. I'd be happy to support her in a contest against Trump. But Bernie has a vision and the proven capacity to inspire voters with it. And unlike Warren, he hasn't been caught in a silly exaggeration about his ethnic background that his opponents can and will use to gain an advantage. That's more than enough to make Sanders the marginally better choice.

Then there is the fact that Sanders is that rarest of things in contemporary progressive politics: a candidate for the presidency who doesn't think in terms of multicultural identity politics. Of course he strongly supports civil rights for women, people of color, the LGBT community, and every other group in the Democratic electoral coalition. But he aims for the left to be more than a conglomeration of intersectional grievance groups clamoring for recognition. He wants to build a broad, unified, class-based movement of working people and the poor marching under a single banner.

That's far healthier, politically speaking, than the more standard Democratic alternative. You might call it a pitch for civic socialism. The emphasis on "civic" helps to explain why he also tends not to agitate for significantly higher rates of immigration. Not that Sanders is an immigration restrictionist. But like most people on the left until about a decade ago, he understands in his bones that enacting a bold domestic agenda requires a sense of national solidarity — and that solidarity dissolves when it expands without limit, to include even those outside the political community.

And finally, there is the issue of international affairs. Alone (so far) among the Democrats currently running for president, Sanders is thinking boldly and creatively about America's role in the world, while also refusing to build bridges to the reflexive hawks who dominate foreign policy thinking in both parties and across the national-security bureaucracy. Where this might lead is anyone's guess, but moving anywhere beyond the monumental waste and futility of the post-9/11 Forever War would be a very welcome development indeed.

My mind may change as the campaign rolls on, and as ever-more candidates jump into the race. But for now, Sanders is the best option on offer for someone looking to bury Trump's brand of right-wing populism for good.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

5 carefully selected cartoons about the Trump-Daniels jury selection process

5 carefully selected cartoons about the Trump-Daniels jury selection processCartoons Artists take on a stress-free life, rare peers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Loire Valley Lodges review: sleep, feast and revive in treetop luxury

Loire Valley Lodges review: sleep, feast and revive in treetop luxuryThe Week Recommends Forest hideaway offers chance to relax and reset in Michelin key-winning comfort

By Julia O'Driscoll, The Week UK Published

-

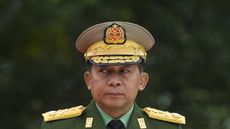

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generals

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generalsTalking Point An armed protest movement has swept across the country since the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi was overthrown in 2021

By The Week Staff Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published